Save our Clandon

National Trust's Plans for Clandon Park

The National Trust’s planning application for work on Clandon Park House

This damaging scheme makes no sense and it must be stopped.

The National Trust claims that the bare brick walls are ‘fascinating, but the house was conceived around its magnificent stucco interiors. Without them, the building has lost its purpose.

The National Trust claims that a reconstruction of the Marble Hall and other state rooms would amount to ‘plastic pastiche’. This shows crass ignorance of the superb work being done by conservation practitioners at the top of their game. A team of freehand plaster modellers did a magnificent job of recreating the ceilings at Uppark after the fire of 1987, some with virtually no original material.

In refusing to reconstruct the interiors and introduce new materials, the National Trust is clinging to an outdated approach which was formulated for very different circumstances. All over Europe and Asia damaged buildings are triumphantly coming back to life. Notre Dame cathedral in Paris is only the latest example. The cathedral is opening its doors again after five years of restoration following a devastating fire.

The fire of 2015 caused substantial harm to the building, and the decision not to restore the interior of the building does nothing to reverse this harm and even makes it worse. The harm done by the proposed development is not necessary to achieve public benefits such as maintaining the building as a visitor attraction. There is no benefit to the proposal which outweighs the harm done to the house. If the important interiors were faithfully restored in an authentic style using authentic materials and the original roof reinstated, this would bring the house back into use and secure its future as a visitor attraction.

The artworks and artefacts which are to be displayed inside the building require a carefully controlled environment, and the cavernous burnt-out space is not suitable for this. New partitions and intrusive display cases will inevitably be necessary for displays within the building. This will damage the character of the interior.

The noise from the pumps and fans will also ruin the tranquility of the grade II Registered Park and Garden and West Clandon Conservation Area.

How to object

You have until 20th December

to submit your objection. Note that there are two planning applications for the same works, so plase be sure to submit two objections. You can submit the same objections to both applications. In order to make an objection, you have to register on the planning pages of Council website (https://publicaccess.guildford.gov.uk/online-applications/registrationWizard.do?action=start)

and log in. Then go to ‘Comment on a Planning Proposal’, write and submit, quoting reference 24/P/01681 for Planning Permission and 24/P/01682 for Listed Building Consent.

You will find the applications here

https://publicaccess.guildford.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?keyVal=_GUILD_DCAPR_208882&activeTab=summary

and here

https://publicaccess.guildford.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?keyVal=_GUILD_DCAPR_208883&activeTab=summary

It is important to object to both applications, and you can submit the same objections to both. Be sure to say what you have to say in your own words

and not to cut and paste. Planning authorities are sensitive to mass-produced objections and will ignore them. However, do feel free to quote from the planning application. Note will be taken of the number of objections made, as well as to their content, so please encourage friends and family who have concerns about the proposals to write in, and send your objections individually, not as a couple.

Clandon Park House, acquired by the National Trust in 1956, is one of Britain’s most important historic buildings, listed Grade 1. Its plain exterior gave little indication of its remarkable interiors and it is these, particularly the ground floor rooms, which gave it its importance. The decorative plasterwork was among the finest in Britain of the early Georgian period. In the Marble Hall, the plaster decoration is complemented by a pair of outstanding chimneypieces with figured overmantels, carved in relief, creating an ensemble of European importance. In 2015 a fire gutted most of the interiors. The Hall chimneypieces, remarkably, survived but most of the plasterwork was destroyed, with the exception of the Speaker’s Parlour which remained largely intact. After eight years of indecision, the National Trust now proposes to conserve the outer walls of the house, which were relatively unaffected by the fire, and to consolidate the interiors in in their fire-damaged state, installing timber walkways for visitor access to the upper floors and a new roof with a viewing platform. Very little restoration is proposed. In particular, it is not proposed to restore any of the lost plasterwork, with the exception of the few fire-damaged sections of the Speaker’s Parlour. The ceilings which collapsed as a result of the fire are not to be reinstated.

Although two applications have been submitted to the planning authority, Guildford Borough Council, they are essentially the same, and the same objections should be raised to both. The first is for Planning Consent for the external alterations to the house, including the new roof, and the second is for Listed Building Consent for the same alterations.

You will find the applications here

https://publicaccess.guildford.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?keyVal=_GUILD_DCAPR_208882&activeTab=summary

and here

https://publicaccess.guildford.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?keyVal=_GUILD_DCAPR_208883&activeTab=summary

Although the applications relate ostensibly to the exterior only, the National Trust’s plans for the interior are dependent on the building services and visitor arrangements which it proposes to create on the new roof. The future of its scheme for the building thus stands or falls by the Council’s acceptance of the proposed alterations and it is vital that anyone who wishes to object to the scheme takes the opportunity to do so here, otherwise it will almost certainly go ahead. Knowing this to be the case, the National Trust has devoted considerable resources to the application. It is accompanied by over 140 documents. The large quantity of this material makes it very difficult for non-specialists to digest. There are, however, documents which give the essence of the proposals, the Planning Statement and the Heritage Impact Assessment. These are quite easy to follow and anyone who wishes to make an objection is urged to read them.

Read the Planning Statement here https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Rd3-qfqLGP5440I_EjF9AXq30iwE64V2?usp=drive_link Read the Heritage Impact Assessment here

The Heritage Impact Assessment claims that restoration is ‘not a practical possibility in most spaces’ without offering any evidence to support this assertion. One of the reasons is that the ceilings are missing or badly damaged and it is not proposed to reinstate them, as noted above. They could, in fact, be reinstated and the ceilings restored, using the numerous fragments of plasterwork which have survived and were collected together after the fire. If these are not in a condition to be re-used, they can be used as models for an authentic recreation. The Heritage Impact Statement goes so far as to say that ‘there is rarely anything to ‘restore’ in the way of decorative plaster, putting the word ‘restore’ carefully in inverted commas. This assertion misuses the word ‘restore’ which the OED defines as ‘to bring back to the original state’. In its pre-application statements the Trust has claimed that restoration is not possible, firstly because there is no accurate record of what has been lost and secondly because there is no one capable of doing the work to the required standard. Both claims are false. Before the fire, the main interiors of the house were well recorded in photography, some of them more than once, and this record, in combination with the surviving fragments, would provided a more than adequate basis for a restoration programme. A great deal of expertise has been developed in the restoration of historic plasterwork in recent years, partly as a result of knowledge gained from the National Trust’s own restoration of Uppark in Sussex after a fire in 1989, and this could be brought to bear in the present case.

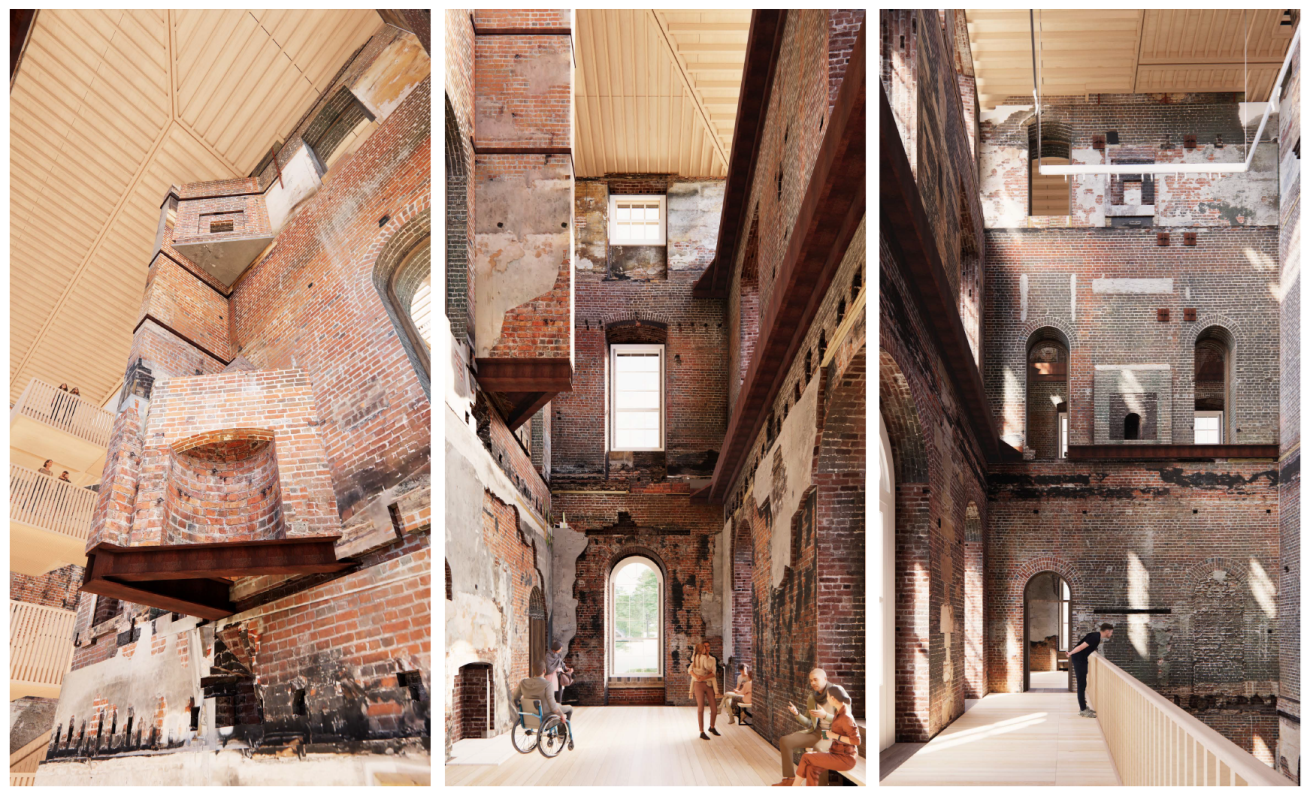

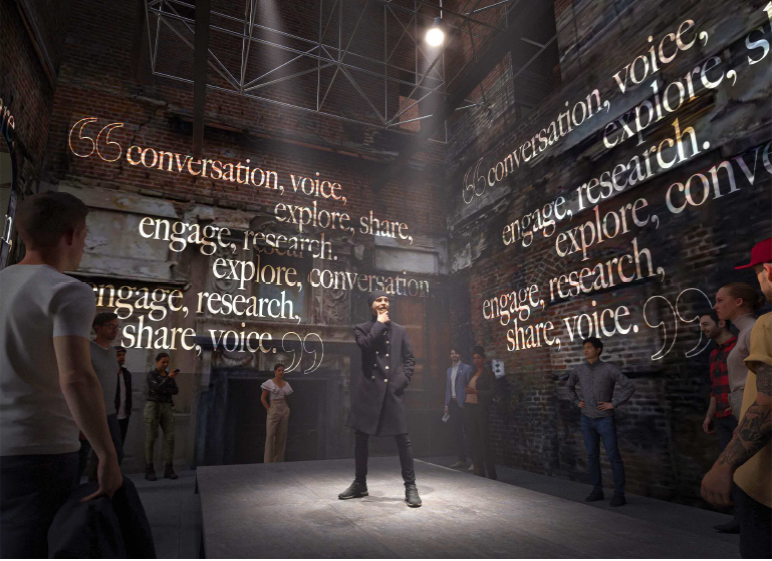

Up to the time of the fire, Clandon had survived largely intact as an early Georgian great house with only minor later alterations. As now conceived it will be filled with visual intrusions in the form of the timber walkways mentioned above which will be needed to give access to the upper floors. A further intrusion will be made with modern display cases which will be used for objects which survived the fire, as illustrated on page 26 of the Planning Statement. On the roof it is proposed to create a modern leisure facility of a kind which is entirely inappropriate to a historic structure of this importance, with a viewing platform and space for a refreshment kiosk.

The question of how the surviving contents of the house will be shown is not discussed in either the Planning Statement or the Heritage Impact Assessment, although it is highly relevant to the proposals. According to the PS, about 600 objects survived the fire. These included some of the house’s greatest treasures. The hangings of the State Bed were fortunately away for conservation when the fire broke out, for example, although the bed itself was damaged. It is implied that some of the surviving objects will be put on display under the new scheme. Many will be environmentally sensitive. Stable environments in the cavernous spaces of the new building will be impossible to create, except by building display cases and controlling the environment inside them. This will be very expensive and difficult to achieve. If the historic rooms of the house were rebuilt, it would be far easier.

Much stress is laid in the application documents in the value of bare interiors as evidence of Georgian building techniques. The fire-damaged structure is indeed of interest, but what it has to tell us could as well be communicated in a series of photographic displays with text. There is no need to leave the building bare in order to show visitors what a bare building looks like. To put such an important building to such humble use shows a tragic poverty of ambition on the part of the National Trust.

A series of supporting statements by bodies who have been consulted appears on pp. 27-30 of the Planning Statement. This is designed to give the impression that the National Trust’s proposals have met with universal approval and the elected members of the Guildford planning committee have no choice but to approve them. The proposals are, in fact, highly controversial, even within the National Trust itself.

The question of cost is not discussed in either of the planning applications. This is normal planning procedure, but objectors should bear in mind that the National Trust received around £66 million from its insurers. They say that they have spent between £20 million and £25 million of this on the salvage operation and on conserving and restoring the brick exterior and that the proposal will involve spending not only the remaining £40 million-odd, but also additional funds from the charity’s reserves. Recreating the original interiors of the state rooms need not cost much more. The reinstatement of the Marble Hall ceiling, the most difficult part of the project, has been estimated at £2.4 million including all overheads. All the rooms would not need to be tackled at once and money can be raised from various sources, something that has not yet been attempted. Once the available money has been spent on unsympathetic modern additions, it will have gone forever. The money should be spent on restoring the most significant part of the house, its fine interiors, while creating training opportunities for the conservation practitioners of the future.

The Planning Statement claims that what it calls ‘the re-making of the mansion house’ will result in ‘a thought-provoking and inspiring place’. This is wishful thinking. The gutted interiors will depress rather than inspire. People will soon weary of the sight of blackened brickwork and plaster fragments and the house will come to be seen for what it actually will be, a disgrace to the Borough of Guildford and a monument to the National Trust’s incompetence and lack of will in refusing to restore the building when it had the means to do so.

Donate

We are raising money though a crowdfunder to be able to oppose the National Trust's damaging plans for Clandon Park.

Please help us if you can.